Nagore Legarreta: ‘There is still some reluctancy to see photography as a true artistic discipline’

2025/09/24

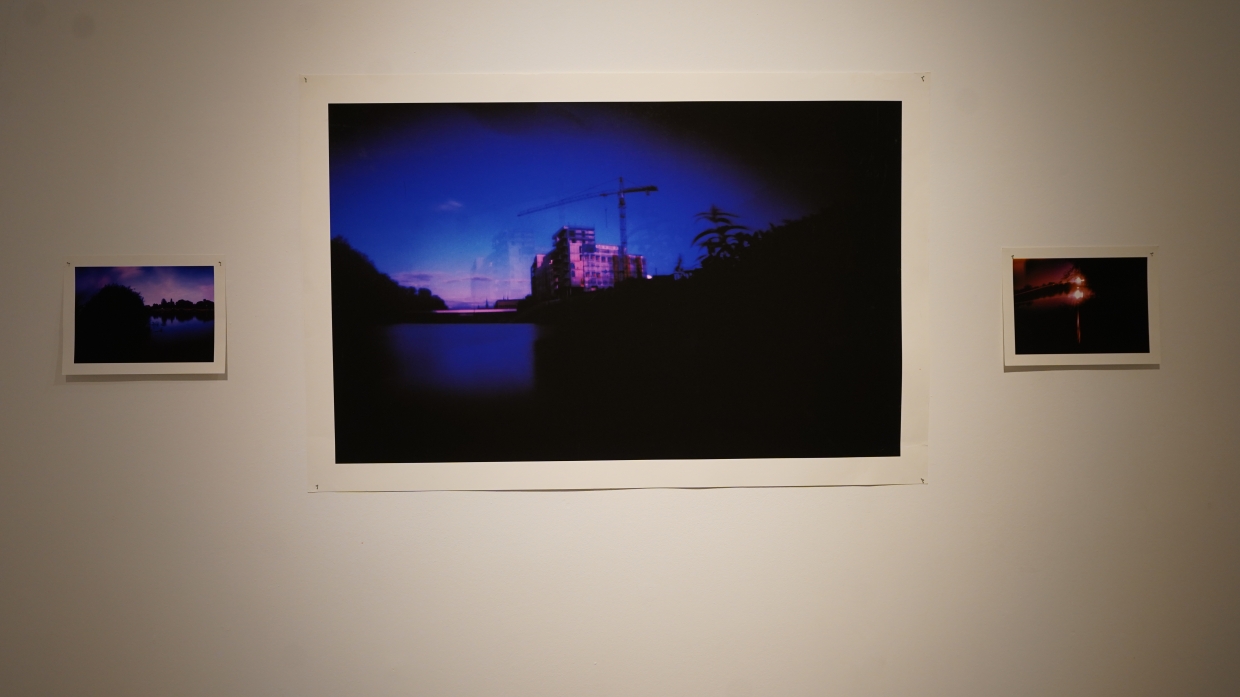

After presenting her collection El río no es un lugar (The River Is Not a Place) at MUNTREF – Museum of Contemporary Art in Buenos Aires, photographer Nagore Legarreta invites us to discover the quiet secrets held on the surface of the river.

Euskara. Kultura. Mundura.

How did you get started and what attracted you most to photography? How did you make the transition from photojournalism to more experimental photography?

I’d say that I’ve always had a creative streak, ever since I was quite young. That dedication to practicing an artistic discipline consistently – researching, working hard, and committing myself – developed in the early 2000s. At that time, the Photographers´ Association was being founded in Hernani, and photographer Alberto Gago was teaching a course there on pinhole photography. He shared with us the possibilities of this technique and the work of several pinhole photographers. That was when I realised this was what I wanted to do, and since then, I’ve been on that path of exploration and research. Now I don´t just do pinhole photography, but that was sparked my interest at the time.

What is pinhole photography based on? What attracted you to this technique and how does it feed into your storytelling?

Pinhole photography is done with a camera without a lens. That is, instead of light entering through a mechanism composed of lenses, it enters through a tiny hole in the camera. The ray of light that passes through the tiny hole and carries the image is recorded on photosensitive material inside the camera: photographic paper, film, X-rays... in short, any surface capable of collecting light.

Although you can get ready-made pinhole cameras, what attracted me at first was the possibility of building them with very few materials: any closed container will do, even a matchbox. Cameras have been created using shoe boxes, red peppers, and so on. Each camera produces a unique effect, and there´s plenty of room for experimentation. And I have to say, there´s a special satisfaction in creating your own camera! It’s a very accessible technique – you can go from having no camera to making one in just a few hours. Of course, analogue photography materials have become much more expensive. When I started out, everything was more affordable.

My work with pinhole photography involves embracing chance. Action, coincidence, improvisation, and hard work have been the driving force behind a lot of my projects. Along the way, other ideas arose, and I experimented with the things I found interesting until they eventually took shape as specific projects – stories I wanted to tell. The technique has given me the opportunity to create in a way that is stimulating and appealing to me.

In the project ‘El río no es un lugar’, the protagonist is the river. What is the artistic process like when you go down to the river?

‘El río no es un lugar’ was born out of a conscious effort to put myself in the river´s place. To capture how it observes us, I began taking photographs from the river´s perspective. I started with the Urumea, because it’s ‘my’ river. I thought that if the river took photos of civilisation, I could imagine how it sees us. So I placed the camera´s viewpoint on the surface of the water, focusing on the shore, observing what was happening on the banks. To do that, I attached the camera to a tripod and used long exposures. I began this exercise in 2015 alongside other creators, thanks to a call for proposals from the Cristina Enea Foundation. I borrowed the phrase “The river is not a place” from the writer Iñaki Segurola. Since the results seemed interesting to me, I still work from this perspective.

Besides the Urumea, you’ve also dived into waters in other places, such as in Poland, Cuba and Argentina. What similarities and differences have you noticed between them?

In recent years I’ve tried to extrapolate the work I started on the Urumea to other rivers. So, for two months, I worked on the Odra River in Poland, where the images I took were really well received. Then came other rivers: the Almendares in Havana, the Ebro and the Nervión in Spain, the Casamance in Senegal, Río de la Plata and the Riachuelo-Matanzas in Buenos Aires, and the Luján River in the El Tigre district of Buenos Aires.

I´ve found that each river offers a unique and powerful perspective for observing the city, social organisation and different ways of thinking. Everywhere I went, I would meet someone who loved their particular river and wanted to show it to me. Through conversation, I was able to understand the history and local landscape of each place. Rivers are linked to issues that cut across our society: economically, they´ve provided transport routes, industrial areas, waste disposal sites and water sources; socially, they´ve divided social classes. Marginalised people from different social structures live on their banks, using the riverbanks as a refuge, and around them history and violence, disappearances and deaths are intertwined, but also food, fishing, vegetable gardens, biodiversity and ecosystems. The river is a fascinating place to explore all of this. And if you can take a dip while you´re at it, all the better, even though many of them are polluted.

Before ‘El río no es un lugar’, you’d worked on several other projects. For example, you were in India working with a camera built from a matchbox.

I ´ve used pinhole photography to develop a number of different projects. Between 2013 and 2017, we organised trips to India with photographers. I couldn´t see myself shooting up close with an expensive camera, so I did some research and discovered that you could build a camera out of a simple matchbox and film. Until then, I´d been working with cameras made from containers, changing the photographic paper each time. The matchbox and film allowed me to take several photos in succession.

My experiences from those trips to India were incorporated into the Project ‘El río no es un lugar’ in a free and impressionistic way. At first, it was just a few photos, but little by little I began to understand what I was doing. In November 2024, I published the photography book ‘Suzko Irudiak’, accompanied by a soundtrack created for the project and an aesthetic inspired by Indian matchboxes, with cover illustration by Ramon Zabalegi.

As for pinhole photography, you´ve taught workshops and classes all over the world. How does that influence your work as an artist?

For me, leading workshops is also a form of creation. Often, reflections you have on your own take shape collectively in these sessions. I need to work alone, but also in a group. Workshops are also a way for me to connect with people with a shared interest in this discipline. I get a lot out of the dynamics of these sessions, because they involve both teaching and learning. I also learn a lot from what each participant contributes, and that shared knowledge is channelled into the group. All of this has an impact on me as a creator and, therefore, on my work.

How much of your creative work is improvisation and how much is planning?

My work is a zikin-brillo, a kind of negotiation between the two. Zikinbrillo was term used by my father to describe how I did things when I was a child. Today, it´s almost become an aesthetic trend. This way of working leaves room for chance to play a role in the process. As a friend once said, “chance is the best designer”. And in part, that´s true, because our minds can be flat when it comes to planning. I don´t like to start a creative process with everything nailed in place, because you can tell that something is ‘‘dulled’’. On the other hand, unexpected things arise from the struggle with happenstance. There comes a point when you need to accept what the process has revealed to you, and that´s when foresight, decision-making, and design come into play. It´s about connecting the initial idea with what you later come up with. From that negotiation, a result emerges – nothing more than the product of the tension built up throughout the entire process: zikinbrillo.

Do you want to know more about basque art? Download this book

In the Basque Country, what would you say are the main opportunities and obstacles today for contemporary photography in the visual arts sector?

When it comes to photography, we´re still quite green, especially when it comes to contemporary photography. This isn´t a phenomenon exclusive to the Basque Country, nor is it the only discipline to be in this situation (contemporary dance and performance art come to mind, for example). It´s significant that there are awards for literature, illustration, visual arts, etc., but we don´t have anything like that here for photography. Photography in the Basque Country has been closely linked to the press, as it has in other places – it’s still difficult to understand it as an artistic discipline. Fortunately, there are places for the development of the art: Gabriela Cendoya´s collection of photography books at the San Telmo Museum, workshops, schools and spaces linked to contemporary photography, such as the IN SITU festival in Vitoria-Gasteiz, Dinamoa in Azpeitia, Black Kamera, IVASFOT, Jolasartea by the Txondorra association, the Artegunea exhibitions at Tabakalera... and many other projects that I’m sure I’m leaving out.

Lastly, looking ahead, what other uncharted territories and techniques would you like to explore in your upcoming projects?

In addition to pinhole photography associated with rivers, I´ve recently been working with other manual techniques. I use cameras that provide more accurate images, but during the printing process, I experiment with manipulation and intervention to help tell my stories. Pinhole photography and my career have given me a language and a style, but now I feel I can apply it to other fields of imaging. I‘m also very happy with the commissions – it’s a wonderful challenge to respond to ideas others suggest, using my own imagination. I really enjoy that interaction; it’s a fertile ground for creating new things.

As for group work, I’d like to create workshops and laboratories where I can work with other people on a fresh vision of photography. Places where we can create our own stories, from our perspective, ensuring that all of this also happens in Euskara. In recent years, I’ve been heading in that direction, and I want to keep exploring it more deeply, looking for allies and resources to help move it forward with integrity.

Etxepare Basque Institute and the artist

The EAS-EZE programme, managed by Bitamine, aims to support the internationalisation of contemporary Basque art by fostering research, production, and the international mobility of artists and creators.

Organised annually, the programme is made possible thanks to the support of the Etxepare Basque Institute, the Department of Culture and Language Policy of the Basque Government, the Department of Culture of the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa, the Contemporary Art Centre of the National University of Tres de Febrero’s museum network (Argentina), and the Basque Government Delegation for Mercosur. This year, the project ´El río no es un lugar´ (The River Is Not a Place) by Nagore Legarreta has been selected as part of the programme to promote contemporary Basque art internationally.